Field Notes: Research Highlights from 2023

The wide array of research interests among UMass historians was on vivid display in 2023, as students and faculty explored their respective interests in museums and archives around the U.S., and the globe. For a few glimpses into a sampling of these exciting projects, read on!

UNSILENCING THE PAST

By Sheher Bano ’23MA

In 1910, while taking a stroll around his family farm with a friend, Kishan Singh came upon his three-year-old son, Bhagat Singh, digging the soil in the fields of Banga (Lyallpur, Punjab). When asked what he was doing, he reportedly said, “I am sowing guns, so that we will be able to fight and get rid of the British.”

This is one of the many stories told, and retold, about Indian revolutionary and freedom fighter Bhagat Singh. As a teen, Singh founded the renowned Hindustan Socialist Republican Army (HSRA), a significant anti-colonial agitator in the 1920s. When Singh was 23, he and his comrades were executed by the British colonial state in the Lahore Conspiracy Case following the assassination of a British official in 1931.

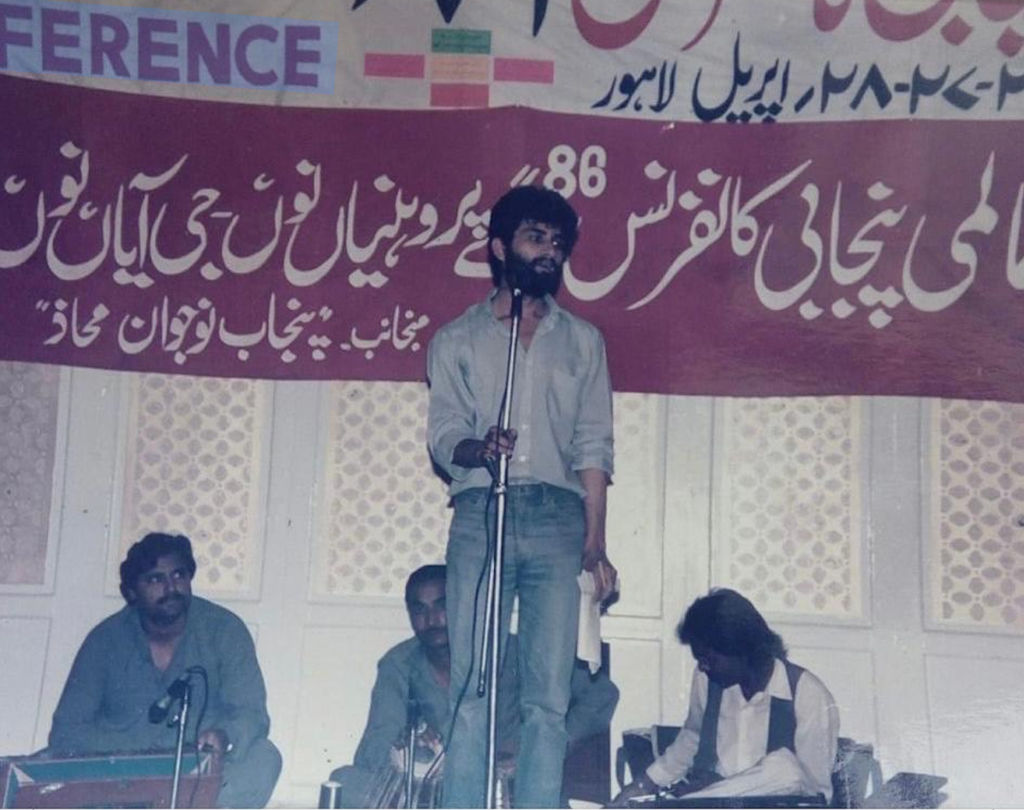

Titled “Memories of Hope and Loss: Kerhi Maa Ne Bhagat Singh Jameya,” (in English: “Which Mother Birthed Bhagat Singh?”), my MA thesis delves into the ways that Bhagat Singh is remembered in post-partition South Asia—specifically the Pakistani side of the province of Punjab. My research draws heavily on oral history and contemporary Punjabi poetry and prose, which I collected, transcribed, and translated during my trips to Lahore in the past two years. I used these sources to argue that Singh’s memory is invoked in contemporary Pakistan to serve a range of political purposes, especially by various groups and individuals who identify as leftists or Marxists. Activists and writers use the figure of Bhagat Singh to highlight the erasure of regional and lingual identities in Pakistan. Their remembrances underline a perceived historical injustice: the imposition of a national identity based on Urdu and Sunni Muslim-ness, which marginalized Punjabi ethno-lingual identities and revolutionary histories. These remembrances challenge Pakistani state narratives, which tend to mute histories that do not serve its interest.

Analyzing the concept of revolutionary motherhood within the literary narratives about Singh, I also demonstrate how mourning and hope coexist in the Punjabi contemporary emancipatory imagination. Such overlaps illustrate how the past is continuously in dialogue with the present, and how the promise of radical hope is woven into the story of Bhagat Singh’s martyrdom.

Sheher Bano is now a doctoral student at UMass Amherst. She was awarded the 2022 History Department Travel Grant, which made her research at Punjab Archives possible. Her research interests include histories of imperialism and anti-imperialism in South Asia; politics of exclusion, erasure, and mourning; and rethinking Third World feminist methodologies.

UNEARTHING ASIAN HISTORY

At the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts

by Catherine Wan

I never gave much thought toward the creation of sources I used in essays. Databases and journal articles were simply online. However, interning at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA) Archives allowed me to be directly involved in the creation of a database. This database, or digital collection, contains all PAFA’s documents on Asian students who attended from 1917 to 1949. As a Chinese American with an interest in Asian American history, I was excited to bring these students out of the files and into the public eye.

A lot of work goes into digitization: scanning; formatting; making sure a document’s size, type, language, and origin are properly labeled; and, finally, choosing the best layout for online presentation. My internship has given me immense appreciation for the work of archivists.

I’ve gotten a taste of the countless hours of work put into digitizing historical documents. And there’s a level of satisfaction in knowing I’ve contributed a bit to the sea of online resources. At PAFA, I’ve held the same pages held by students decades ago, turning them from crumbling paper into something that will outlast even myself.

Catherine Wan is a sophomore majoring in history and legal studies. As a Philadelphia native, she was particularly excited to intern at such an important historical institution as the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts.

ABOUT THE PROJECT

Over the course of her internship, Catherine Wan researched, digitized, and cataloged academic files from students of Asian descent who attended the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts from 1917–1949. She also curated a digital history project bringing these hidden histories to light. Highlights from her research—including a timeline, profiles, primary sources, and more—are featured on PAFA’s website. Check out her project here.

THE VICTORY OF VIOLENCE

Depicting War on the Column of Marcus Aurelius

by Timothy Hart

This engraving comes from the narrative frieze that spirals up the length of the Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius’s monumental victory column in Rome. Completed after the emperor’s death by his son Commodus, the column celebrates Rome’s Marcomannic Wars, which were waged from 166 to 180 CE against an alliance of peoples who dwelt on the northern banks of the river Danube. Depicted here is a scene of intentional terror wrought by the Roman army. We see a Marcomannic village set ablaze by Roman troops while the inhabitants are rounded up for enslavement. The scenes on Marcus’s column tend to depict the cruelties of war with an unflinching eye, which historian Elizabeth Wolfram Thill suggests sets it apart from the less violent scenes of conflict on the slightly earlier column of Emperor Trajan.

In the second chapter of his forthcoming book, Beyond the River, Under the Eye of Rome, Timothy Hart argues that the explicit violence and terror depicted on Marcus’s column both reflects popular sentiment toward the Marcomanni at the time and illustrates imperial support for this dehumanization of Rome’s Transdanubian neighbors. Hart explains that concurrently with the Marcomannic Wars, the Roman world was ravaged by a deadly pandemic known to scholars as the Antonine Plague. Faced with incurable disease bringing death to the heart of Roman cities, the wars along the Danube offered a chance for Marcus Aurelius to prove his ability to lead and protect his people by eradicating the “barbarian” menace. Thus, despite repeatedly seeking peace with the empire, the Marcomanni and their allies suffered more than a decade of death and enslavement to ease the minds of a fearful Roman public. In the frieze of Marcus’s column, we see the Marcomanni receiving what they “deserved” after years of demonization as Rome’s designated enemy.

Marcus’s victory column is just another tourist stop in Rome today, but a closer look at the monument’s frieze reminds us of some hard truths the tour guides usually omit: The Roman state was often a brutal agent of imperial oppression, and emperors—even those deemed “good” by posterity—were often deeply complicit in that violence.

Timothy Hart is a lecturer in the history department, where he teaches courses on a range of subjects related to ancient Mediterranean and Near Eastern history. His research focuses on the ways Greek ethnographic theory and writing influenced Roman perceptions of, and actions toward, peoples dwelling beyond the imperial frontiers.

INTERPRETING ELIZABETH FREEMAN

Centering the Woman, Not the Myth

By Reid Ellefson-Frank, in cooperation with Marcus Smith, Jaehee Seol, Jamie Mastrogiacomo, and María Portilla Moya

In 1781, Elizabeth Freeman brought suit against her enslaver, Col. John Ashley, on the grounds that slavery went against the new Massachusetts state constitution. In doing so, she became the first person in Massachusetts to win her freedom on the grounds of constitutionality. After her emancipation, Freeman did domestic labor, served as a midwife, and became one of the most prominent Black property owners in Berkshire County.

During the 2022–23 academic year, a team of UMass public history graduate students worked with the Du Bois Freedom Center in Great Barrington, Mass., to develop text for an interpretive sign about Elizabeth Freeman. Unfortunately, most of what historians know about Freeman comes from her employers, the Sedgwick family. The narrative the Sedgwicks established is highly proprietary, claiming Freeman as a member of their family and overemphasizing their role in her life while downplaying her chosen and blood relations. We saw this project as an opportunity to join more recent scholarship centered on Freeman’s bravery, resistance, agency, and community. Freeman’s actions were remarkable; she dared to turn the apparatus of government against itself at no small risk to her personal safety. She initiated the chain of events that would lead to the abolition of slavery in Massachusetts.

In writing this script, we had to grapple with biased primary source documents and gaps in the historical record, which routinely excludes enslaved people’s perspectives. The UMass public history team was honored to work with the Freedom Center and to offer our interpretation of Elizabeth Freeman’s story.

Reid Ellefson-Frank is a public history certificate student interested in archaeology, the politics of memory, and how public history can be an agent of social change.