By Amelia Yeager

As historians, we are too often confronted by gaps in the archive — missing details or even figures who went unrecorded, but whose presence could answer so many questions. Last summer, I combed the archives for a freed African woman whose inclination toward posterity would, with plenty of digging, reveal her connections within the cultural and intellectual circles of Revolutionary New England.

Like many public history students, I had been entranced by Tiya Miles’s All That She Carried during my first semester of graduate school. In David Glassberg’s Public History course, we discussed how Miles created such a stunning history with, at first, only one piece of evidence: a sack embroidered by the descendant of the enslaved girl who carried it. I found myself similarly taken with Marisa J. Fuentes’s Dispossessed Lives, a study of free and enslaved women of color in eighteenth-century Bridgetown, Barbados. Fuentes used a methodology she termed “reading along the bias grain” to extract details of women’s experiences who were silenced by the archive.1 In doing so, she recreated a tapestry of mobility and agency among women whose lives, in their time, weren’t deemed worthy of recorded history.

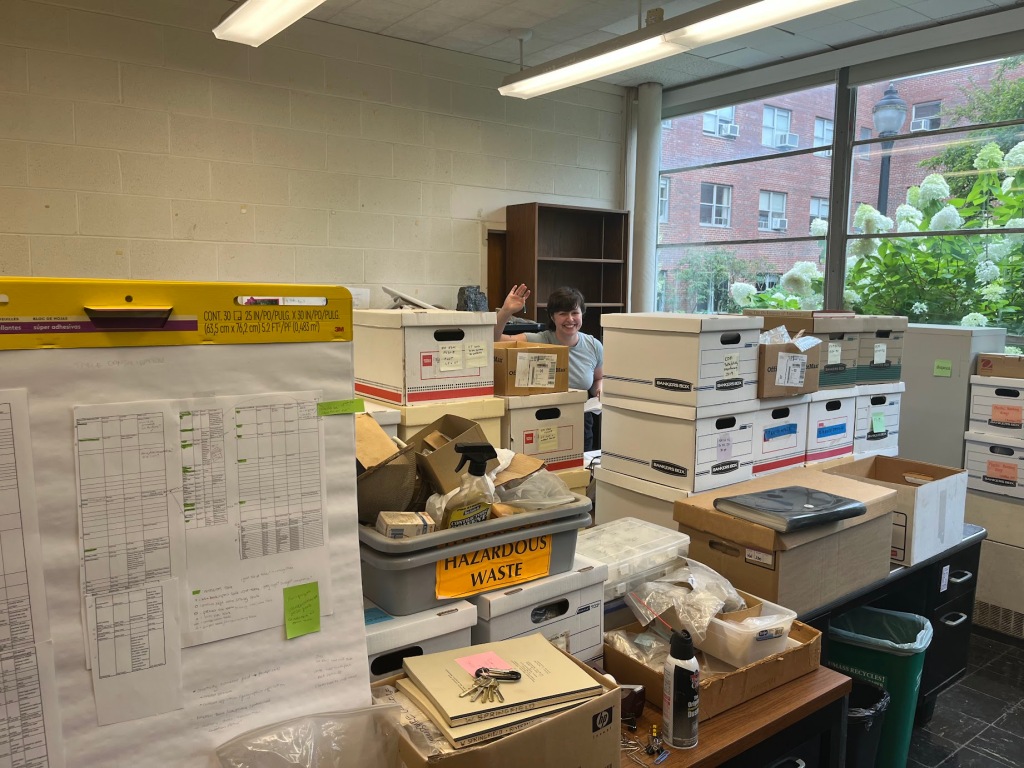

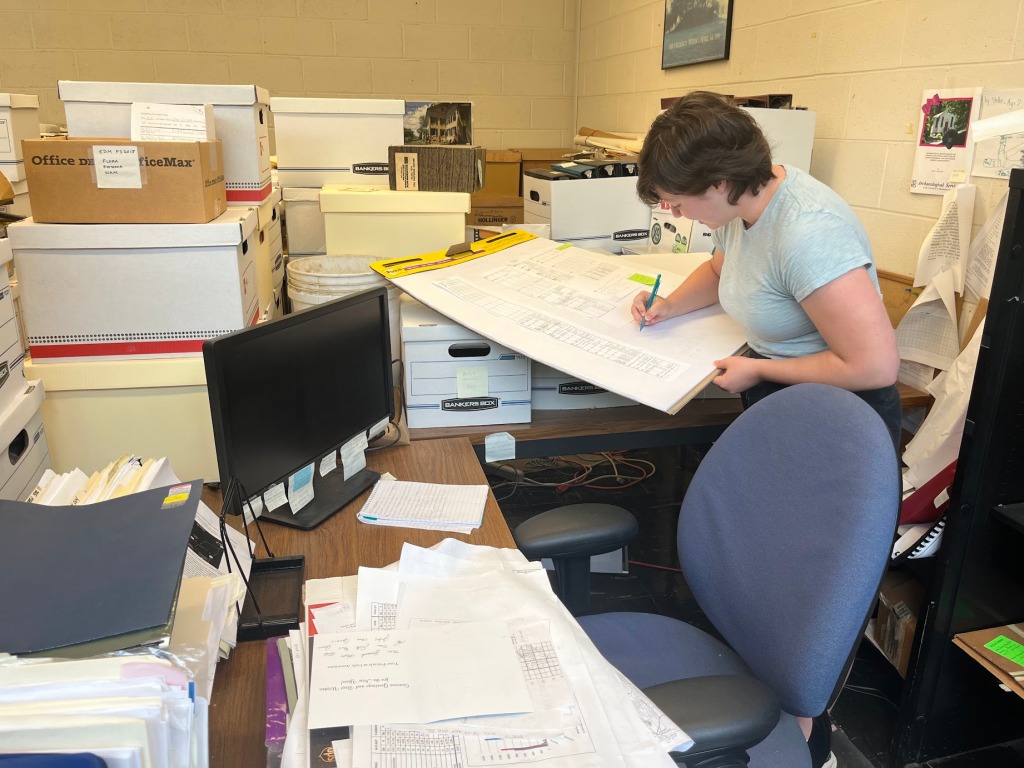

During the summer of 2023, I worked as a Buchanan Burnham Fellow at the Newport Historical Society (NHS) in Newport, RI. The fellowship was the perfect opportunity to apply my coursework at UMass to a historical organization and put some of the theory I learned during my first year into practice.

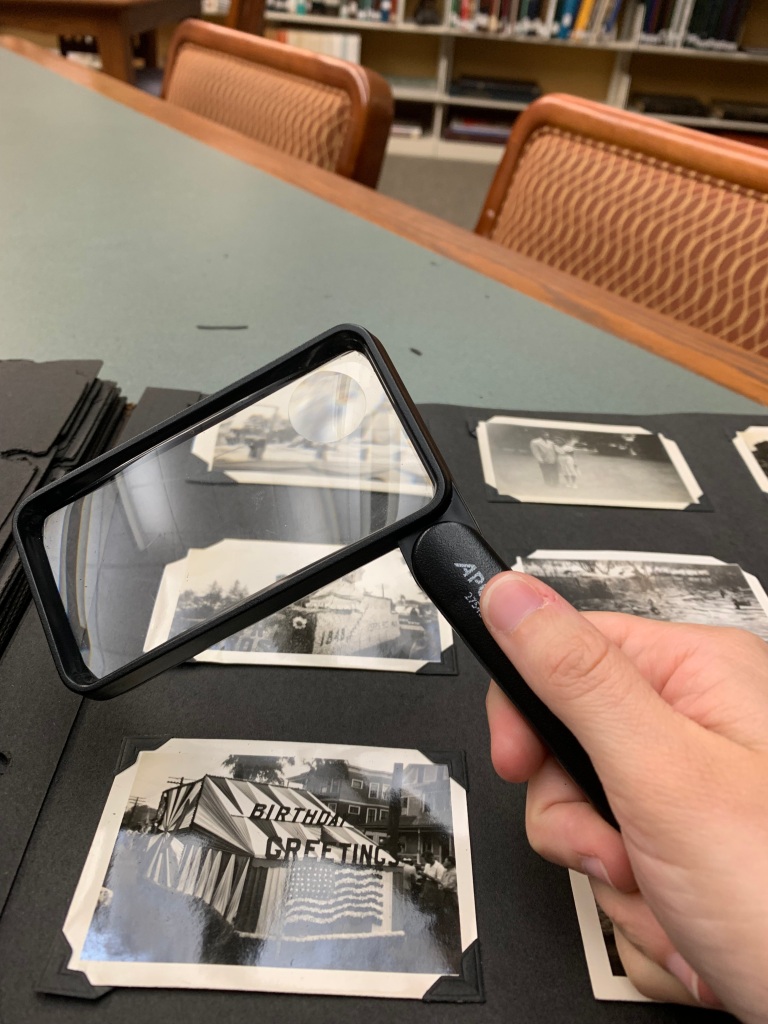

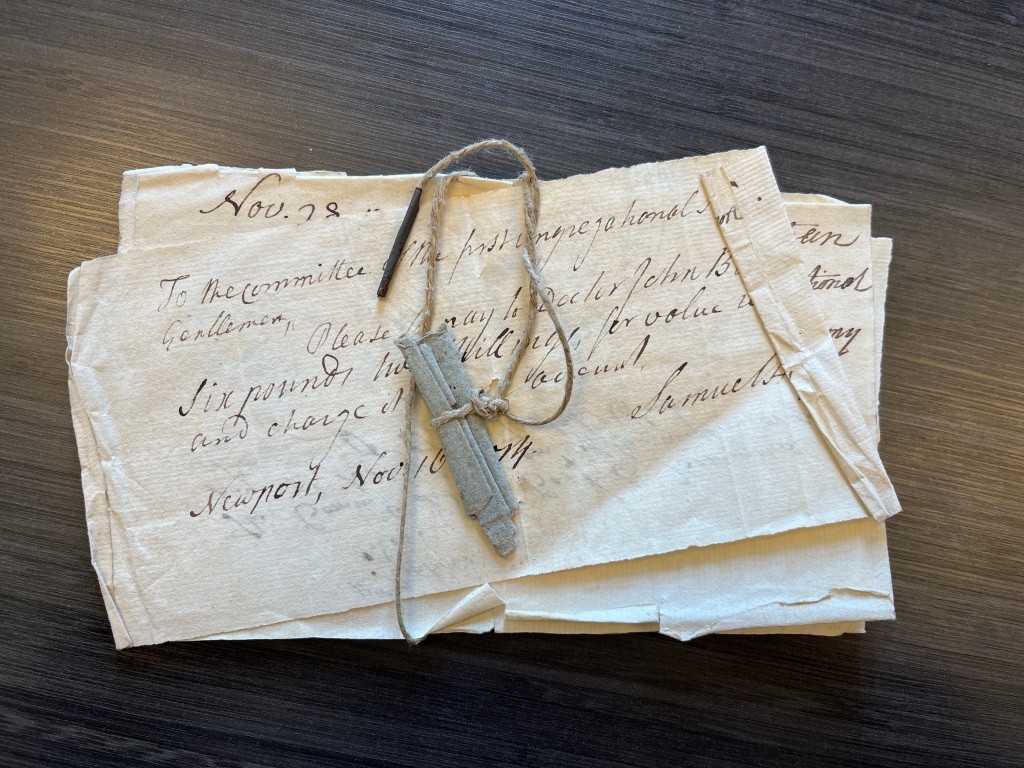

The NHS archives, which occupy a library, a vault, and a vast basement, presented so many documentary curiosities and paths for independent research that it was almost overwhelming. Among church records, early censuses, and decades of city directories, I caught glimpses of people whose stories weren’t recorded in any biographies or scholarly articles. It was the perfect opportunity to read along the bias grain.

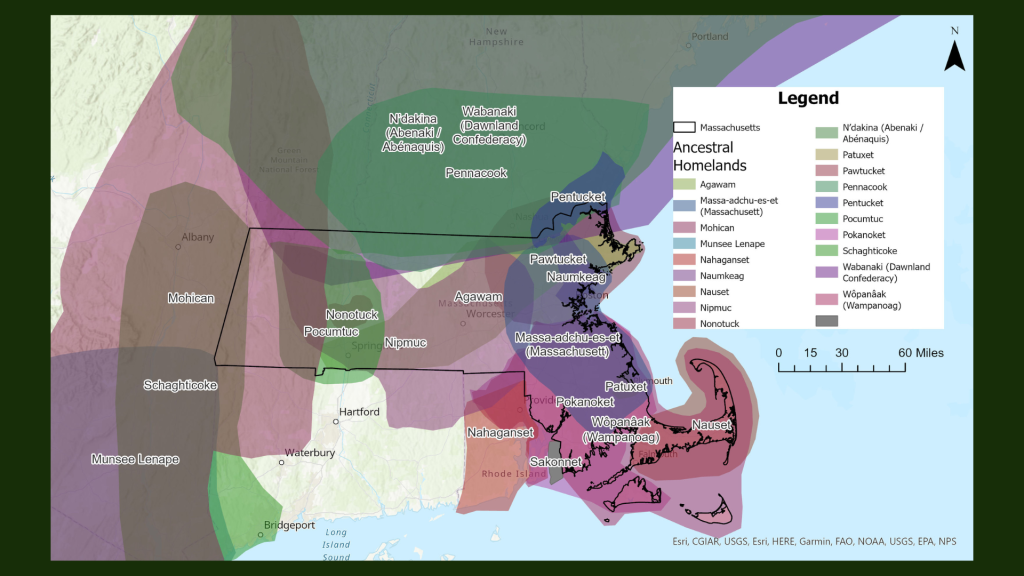

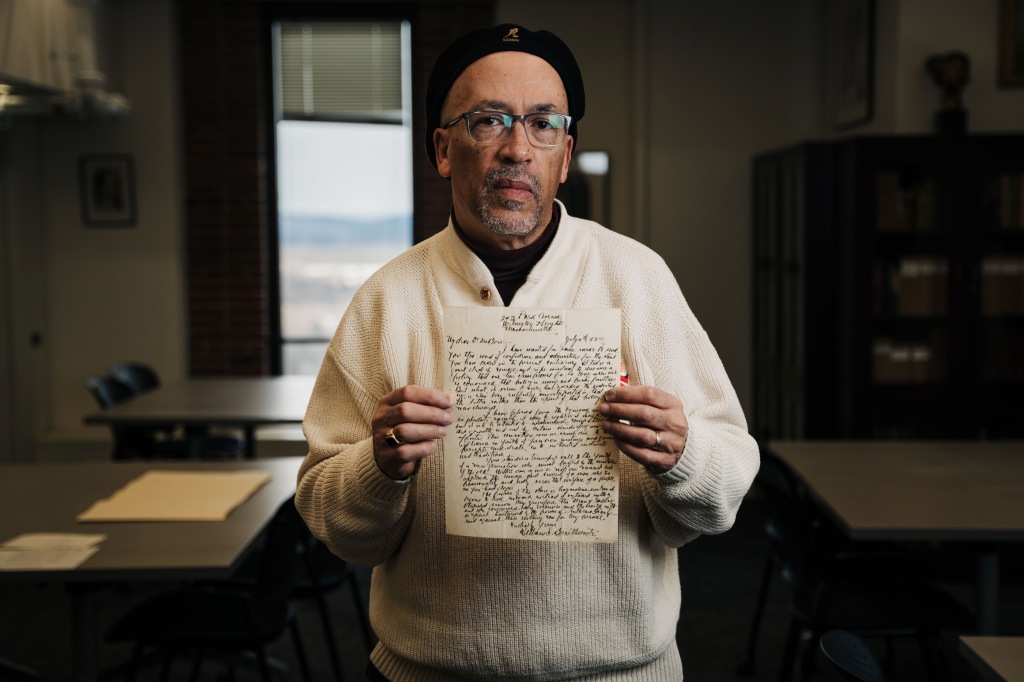

One of the names that arose was Obour Tanner Collins. According to the NHS’s records, she was a member of the First Congregational Church (FCC), enslaved in the 1760s-1780s by James Tanner and later his widow Hannah, and married to Barra Collins in 1790. The most intimate and best-known historical evidence of Obour Tanner Collins is her correspondence with Phillis Wheatley Peters, the famous poet who published her first poem in the Newport Mercury in 1767. At the time, Wheatley was enslaved in Boston, and she maintained a correspondence with her friend Obour in Newport from 1772-1779, at least. We have these dates as bookends because an elderly Collins gave six of her letters from Wheatley to Katherine Edes Beecher, the wife of her pastor at the FCC, in the early 1830s.2 Beecher passed them along to a Reverend Hale who donated them to the Massachusetts Historical Society, where they are available online.

Unfortunately, we have only one side of the correspondence between Wheatley and Collins. Even though none of the letters written by Collins survive, a picture of her emerges from Wheatley’s writing. The two friends were both literate, devout Congregationalists, and shared several mutual acquaintances — enslaved and free — in New England. The most striking part of their relationship is that Collins is likely the only friend who was truly Wheatley’s peer. Both were kidnapped and enslaved as children, an experience that Wheatley’s elite white patrons sensationalized and exploited, but could not share. To the famous poet, Collins was a “sister.”3

When I drove back to Amherst in August with a summer of research behind me, I knew there was more to be found — and to be said — about Obour Tanner Collins. She is proof that the millions of enslaved people whose stories are absent from the archives lived deeply meaningful lives.

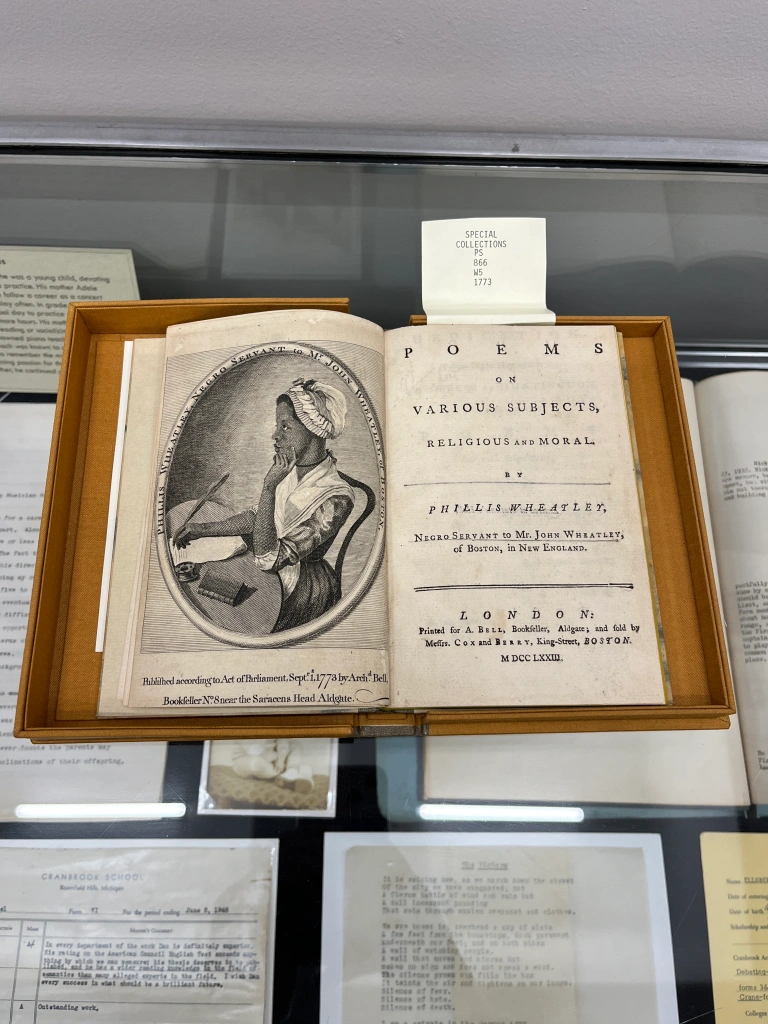

I decided to continue researching Collins, specifically in the context of her role in Phillis Wheatley’s campaign to secure subscriptions for her first and only book, Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral, in the early 1770s. On October 30th, 1773, Wheatley sent Tanner copies of her book proposal and asked her friend to “use your interest to get Subscriptions as it is for my Benefit.”4 The trust that Wheatley put in her friend to secure subscriptions (of which she needed 300 to print the book) attests to Collins’s connections within her Newport community.5

Tracking down the six copies Collins sold — in other words, performing literary genealogy — can reconstruct an understudied part of Revolutionary Newport and assert her centrality within it.6 Luckily, my search is beginning close to home: UMass acquired a first edition of Wheatley’s Poems as the Library’s two millionth volume in 1984.7

Ultimately, like any good historical inquiry, this research raises more questions than answers. Who exactly ordered copies of Wheatley’s book through Collins’s campaign, and how did she persuade them? What kind of connections did she leverage to convince them to subscribe, and how did her enslavers or their peers view her connection to a famous writer? And in terms of surviving evidence for all these connections — what happened to the books?

Beecher wrote in the donation note that accompanied the letters to the MHS in the 1860s, “I have no doubt that many copies of it (Wheatley’s book) are still extant among the old residents in Newport” — and she may have been on to something!8

The most obvious connection is to the FCC, whose records list a copy of Poems purchased for the church by Rev. Samuel Hopkins in 1774.9 Wheatley mentioned Collins in multiple letters to Hopkins, claiming that the two women were “living witnesses” to the ability of Africans to accept God, and his son regularly carried letters between Newport and Boston.10 Another possibility is that the African community, which organized into mutual aid societies in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, pooled their money to purchase a copy to circulate (something they would do with lottery tickets and with other books).11 Finally, in the 1880s, two first edition copies of Poems were listed in the estate of Dr. David King, who lived on land purchased from Collins by his father in 1831.12

While it may be impossible to definitively track down each of the six copies that Collins sold on behalf of her Bostonian friend, researching the books reveals how an enslaved African woman was connected through literary networks across the Atlantic. Regardless of her relative absence from the archival record, Collins’s contribution to a literary legacy we enjoy today is remarkable.

I will be presenting this research at the National Council on Public History’s 2024 Annual Meeting in Salt Lake City, UT, during the poster presentations on April 11th. Come see me! After that, I’ll be working on turning the project into a longform piece of writing.

Amelia Yeager is an M.A. student in History at UMass Amherst who is also pursuing the Public History Graduate Certificate. Her 2023 internship was supported by the Charles K. Hyde Intern Fellowship.

- Marisa Joanna Fuentes, Dispossessed Lives: Enslaved Women, Violence, and the Archive, 1st ed, Early American Studies (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016), 9. ↩︎

- “November Meeting. Death of Lord Lyndhurst; Death of Hon. William Sturgis; Dr. Ephraim Eliot; Diary of Ezekiel Price; Letter of Count de Marbois; Phillis Wheatley; Letters of Phillis Wheatley,” Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society, 1863-1864 7 (November 1863): 268-269, footnote. ↩︎

- Phillis Wheatley, “Letter from Phillis Wheatley to Obour Tanner, 10 May 1779,” May 10, 1779, Massachusetts Historical Society Collections Online, https://www.masshist.org/database/viewer.php?item_id=778&br=1. ↩︎

- Phillis Wheatley, “Letter from Phillis Wheatley to Obour Tanner, 30 October 1773,” October 30, 1773, Massachusetts Historical Society Collections Online, https://www.masshist.org/database/viewer.php?item_id=773&img_step=2&br=1&mode=transcript#page2. ↩︎

- Phillis Wheatley, The Collected Works of Phillis Wheatley (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988), 188-189. ↩︎

- Phillis Wheatley, “Letter from Phillis Wheatley to Obour Tanner, 21 March 1774,” March 21, 1774, Massachusetts Historical Society Collections Online, https://www.masshist.org/database/viewer.php?item_id=775&br=1; Phillis Wheatley, “Letter from Phillis Wheatley to Obour Tanner, 6 May 1774,” May 6, 1774, Massachusetts Historical Society Collections Online, https://www.masshist.org/database/viewer.php?item_id=776&br=1. ↩︎

- John Kendall, PS.866.W5.1773 Acquisition File, University of Massachusetts Amherst Special Collections and University Archives. ↩︎

- “November Meeting,” 268, footnote. ↩︎

- First Congregational Church Records, MS.123 Box 1, Folder 19, NHS Collections. ↩︎

- Wheatley, Collected Works, 176. ↩︎

- Book of Records of the African Union Society, 1787-1796 (vol.1674B), NHS Collections, 63-64; Book of Records of the African Union Society, 72-73, 254; Minutes of the African Union Society & African Humane Society, 1793-1810, (vol.1674C), NHS Collections, 41. ↩︎

- George A. Leavitt & Co., Catalogue of the Library of the Late Dr. David King, of Newport, Rhode Island, 3 vols., Harvard College Library Preservation Microfilm Program 02444 (New York: G.A. Leavitt, 1883), 263; Letters of Edward King, NHS Collections, 7; Newport Land Evidence 18: 356-357. ↩︎